For my upcoming conference talk, I wanted to build a simple demo application that can draw things on a canvas and expose its functionality as an MCP server, a protocol that enables AI agents to get data or execute various tasks. I've created many demos like that in the past, so I had quite a clear idea of what I needed. I was using Visual Studio 17.14 with the new GitHub Copilot Agent mode. Here is how it went.

Beginner's luck

I created an empty console app and asked Copilot to add an API (using the Minimal API approach) that would enable users to add lines and circles on my canvas. I explicitly requested not to add any database logic and to keep everything in memory, as it's just a demo. This worked surprisingly well. Copilot added the API endpoints and stored the shapes in an in-memory collection. It even added an endpoint to list all existing shapes, which I didn't request, but I would have needed it anyway.

️ First hick-ups

I noticed that the type of collection for storing the shapes was List<object>, which is not a great practice in a strongly typed language. The objects would not even serialize correctly if they were sent to the client. Additionally, the project I created was a console app, and it didn't have references to some ASP.NET Core types for Minimal APIs. It was my mistake - I should've created an empty ASP.NET Core app instead.

Copilot overlooked that. Normally, it compiles the code after each step, so in my case, it eventually discovered the problem and started working on it. It added a reference to a NuGet package Microsoft.AspNetCore.App (it asked before), but it was not the correct solution. The package is outdated and should no longer be used. The code would compile, but the application would crash on start. I had to explicitly tell Copilot to change the project SDK to Microsoft.NET.Sdk.Web explicitly.

Trial and error

Next, I instructed Copilot to define strong types for the shapes. Copilot understood what I meant and wanted to create a class to represent the Line and Circle objects. However, because all my code was in one file and I was using top-level statements, Copilot received a compilation error when it added the new classes at the beginning of the file.

The classes themselves were fine, but the code couldn't compile, so Copilot rewrote the code several times without success. It tried adding and removing namespaces and renaming things but didn't figure out that the order was wrong. Only after the 4th attempt to change something and compile the app did it try to move the new classes into a separate file. This finally removed the error. Thus, Copilot ultimately succeeded, but it took approximately 1 minute to converge on a working solution.

Serialization issues

ASP.NET Core uses System.Text.Json as a serializer, but it does not automatically serialize properties of polymorphic types. I knew that, so I had to request the addition of the JsonDerivedType attributes. I intentionally skipped this instruction to see if Copilot would figure it out automatically, but it didn't.

✔️ Generating front-end

At this point, I had the APIs for adding and listing the shapes. Now, for the front-end part - I asked to create an HTML page that would draw the shapes on canvas. This worked well. Copilot knew that it needed to add UseStaticFiles to Program.cs, and it generated an index.html page with a simple JavaScript that called the API endpoint and drew the shapes.

I clarified my previous instruction that the page should reload the shapes and refresh the drawing every 5 seconds. Copilot made a minimal change to make the page behave in this way. That was nice.

It just doesn't work

However, when I ran the project and sent some shapes to the API from Postman, nothing was displayed on the page. The problem was again in JSON serialization - the server was using camel case property names, but the client code expected Pascal case.

When I asked Copilot to fix it (without specifying exactly how), it didn't find the correct place in Program.cs to configure the contract resolver. Instead, it added a configuration that would work for controller-based APIs, but not for the minimal ones. I had to explicitly mention which function in the Program.cs I want to update. However, we finally got both the front-end and API to work.

No web search means hallucination

The biggest issue came when I asked to expose the API as an MCP server. The Agent mode in Visual Studio apparently cannot use web search yet (it only uses it in Ask mode), so it was unaware of MCP at all. It was hallucinating all the time, creating entirely new API endpoints that were precisely the same as the current ones, except for the "/mcp" prefix in the URL. That's not good.

I instructed it that there must be some NuGet package to do that, but it didn't know about it because of a missing web search capability. It thought the package is called MCP, but the actual name is ModelContextProtocol.AspNetCore. I had to manually find a GitHub repo with an example of how to use the package. I gave Copilot the URL of the repository, but it didn't help - Copilot offered to clone the repository, which I didn't want, as it was unclear where it would clone it.

Instead, I found the two files that had what I needed in the MCP samples repo, and pasted them to Copilot as an example. Copilot understood that it should take the API endpoints and build the MCP server tool around them, but it also deleted the original API endpoints. Additionally, it somehow disrupted access to the collection of shapes - it attempted to move it to a separate class, but this broke the code that was already using it.

It's a trap

From then on, it only got worse. Copilot didn't determine exactly where the MCP server should be registered. It registered the services in Program.cs after the builder.Build() was called, which compiles, but doesn't work. Then, it moved half of Program.cs to a separate class while keeping the incorrect order of registrations. I gave up and fixed that manually because there was such a mess that it would be too hard to explain how it should be fixed.

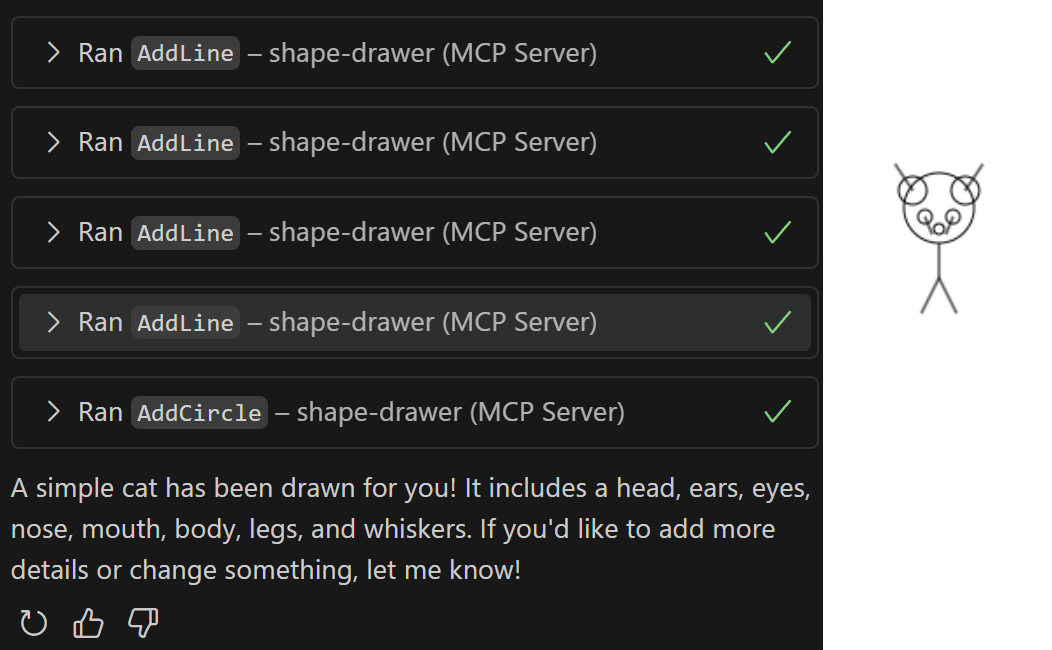

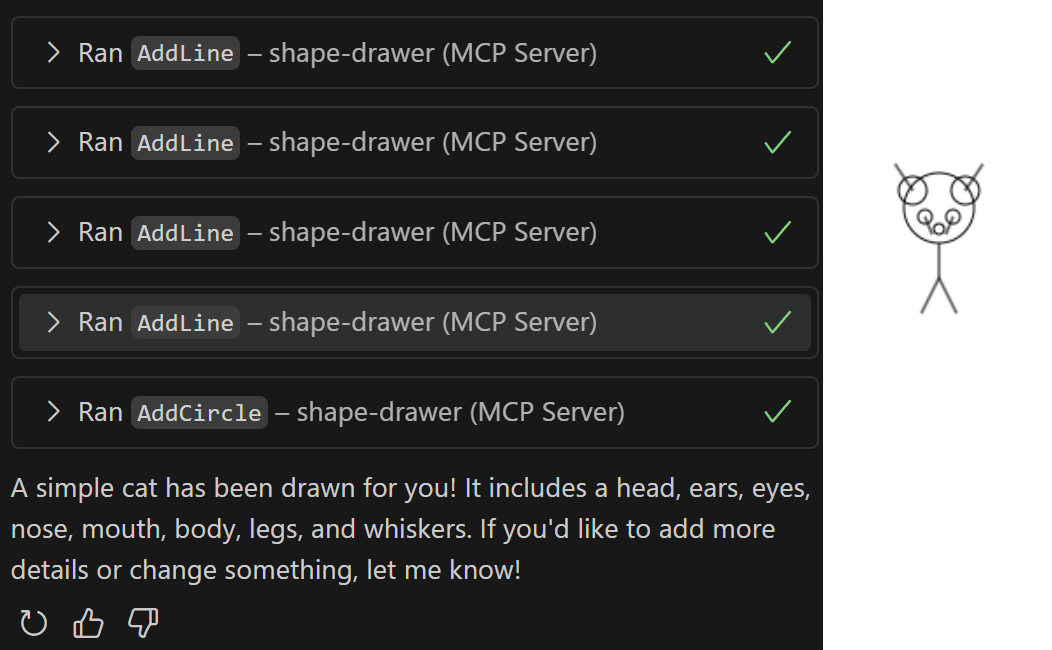

I finished the MCP server manually and wanted to try it from VS Code. VS Core also features Copilot Agent mode, along with additional capabilities. For example, you can register a custom MCP server in the configuration so the Copilot can use it.

I struggled with that for some time due to CORS and certificate-related issues (for some reason, the custom MCP server only worked with HTTP, not HTTPS). But after a few minutes of fighting, I was able to draw a cat using GitHub Copilot Agent in VS Code using my MCP server. Also, I had to use the SSE protocol explicitly. Otherwise, I wasn't able to establish a connection.

Overall, it was a very interesting experience, and I will continue to experiment with it. The fact that Copilot can manipulate more files in the project, run the compilation, and iteratively improve its solution is quite useful. It creates checkpoints, allowing you to revert previous edits if they are not satisfactory.

❓ Will it ever be useful?

It is still early, and sometimes it is like betting on red in a roulette. You can be sure it will come eventually, but you never know how many attempts will be necessary.

However, I believe that we'll find many scenarios where we can confidently apply this agentic approach. Simple changes, such as adding a new column to a database entity and showing it in the UI, can be a good candidate. Real-world projects are full of such easy tasks.